Public realm as opportunity for learning and negotiating

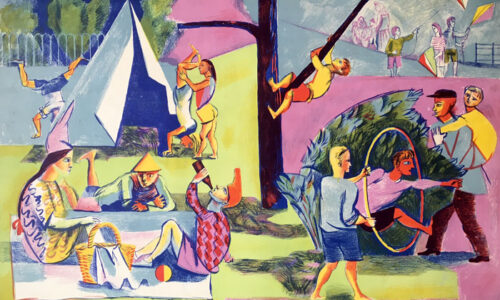

Public space – as life, in all its joy and discomfort

Inspired by a current project, Circus has been reflecting on what tomorrow’s public realm might be. How does it evolve over time and what role does it play within cities, within quarters and neighbourhoods. What does the public realm say about our society, and our values? Much inspired by the work of Richard Sennet, I have been reflecting on my own reading of a city and the promises of the public realm.

Skirting the hustle and bustle of a sunny afternoon on the bank of the Thames, I suddenly found myself in soundlessness – a very quiet and still space in the corner of the city, known as ‘old paradise gardens’. This I discovered, is one of the oldest public open spaces in Lambeth. It intrigued me – perhaps because I was alone, the atmosphere, the history, the imaginings of a smog-soaked London and an old world. It was once both a recreation site and a burial ground. A place of joy and grief, play and pain, life and death.

And as I wandered and pondered, I thought – public spaces allow life to be celebrated, in all its pleasure and discomfort. As Richard Sennett once said, “a city should be a school for learning to live a centred life” – and this can’t be achieved if our urban designs limit such opportunities for learning, for difference, for unpredictability.

Public space – as open, democratic and discursive

The public realm can be a place of rubbing shoulders with strangers, of muddling along, relying upon, learning of and surviving with – each other.

Open spaces provide opportunities for understanding those around us, for learning of different perspectives and principles however far they are from our own. And it is in this understanding, that we might find common ground – a place where the dividing walls are a little less robust, and the paths wind closer towards progress.

Cultural theorists and philosophers Richard Sennett, Hannah Arendt and Jürgen Habermas, however much they differ in argument and perspective, are all in favour of open public spaces – whether physically or discursively. Public spaces must provide opportunities for “contestation and negotiation,” for debate and for learning of one another.

And this is more important today, than ever before. Thinking about the internet – ‘a digital public realm’ – we curate online worlds for ourselves that are predictable and digestible. As Sennett argues, human beings will never choose disorder – it is not in our nature. And if we do read anything that doesn’t quite fit the world we’ve designed, the technologies of today offer a swift and easy response – blocking, unfollowing, ‘cancelling’.

Which is why, tomorrow’s public spaces – in the physical world – offer opportunities for interaction and confrontation. They cannot become like the echo chambers and digital worlds we wrap around ourselves. The public realm can be vibrant, discursive, diverse, dense, unpredictable – where every vibration is different from the one before.

Public space – as planned and unplanned

“A good city resembles a pizza, not a doughnut” – Richard Sennet.

Urban planning can plan to be unplanned, democratised and affordable. There is opportunity to make use of the 270,000 abandoned properties in the UK today. To introduce price controls on the private rental market so people are not increasingly priced out to the peripheries. To more successfully and humanely repurpose empty offices as residential spaces – spaces that actually ‘feel like home’. To keep inner cities alive and for all. Frank Lloyd Wright once described his hopes for a ‘vertical street’. Imagining this, repurposed office blocks can be what Sennett describes as ‘ville’ – a series of customs, impressions and indefinable qualities – not bricks and mortar alone. In today and tomorrow’s world, this could be achieved through intergenerational and co-living initiatives, where shared amenities, facilities and communal spaces are intentionally built into the environment. Our clients are considering, for example, how we might recreate the atmospheres and encounters of a town-square from the ground up, floor to floor?

There is a real opportunity and necessity for urban planning to be intentionally open and confrontational – a place where different human states can collide – joy, discomfort, pain, hope. So that streets and places are not mere thoroughfares, but engaging social spaces, where spontaneous, life-giving encounters thrive.

Public space – as partner and friend

Circling back to where we started in ‘old paradise gardens’ – in old 18th century London – it’s perhaps apt to end with a lasting thought by one of the ages most well-known voices, Charles Dickens:

“When I enter a great city by night, every one of those darkly clustered houses encloses its own secret; every room in every one of them encloses its own secret; every beating heart in the hundreds of thousands of breasts there, is, in some of its imaginings, a secret to the heart nearest it!”

It is hopeful to think what would be, if people left those darkly clustered houses to bump into, to meet, play, grieve, confront, laugh, and just be, out in the open public spaces of tomorrow – who knows what we might learn of others, reveal about ourselves, and work towards, together.

Written by Esther Mason

April 2025

Photo credit: In the Park, 1937 – Robert Medley